Image Credit: From The Source

'My Demise As Journalist Unsurprisingly Coincides With Death Of Journalism In General In This Country': Author C P Surendran

India, 24 Oct 2021 12:49 PM GMT

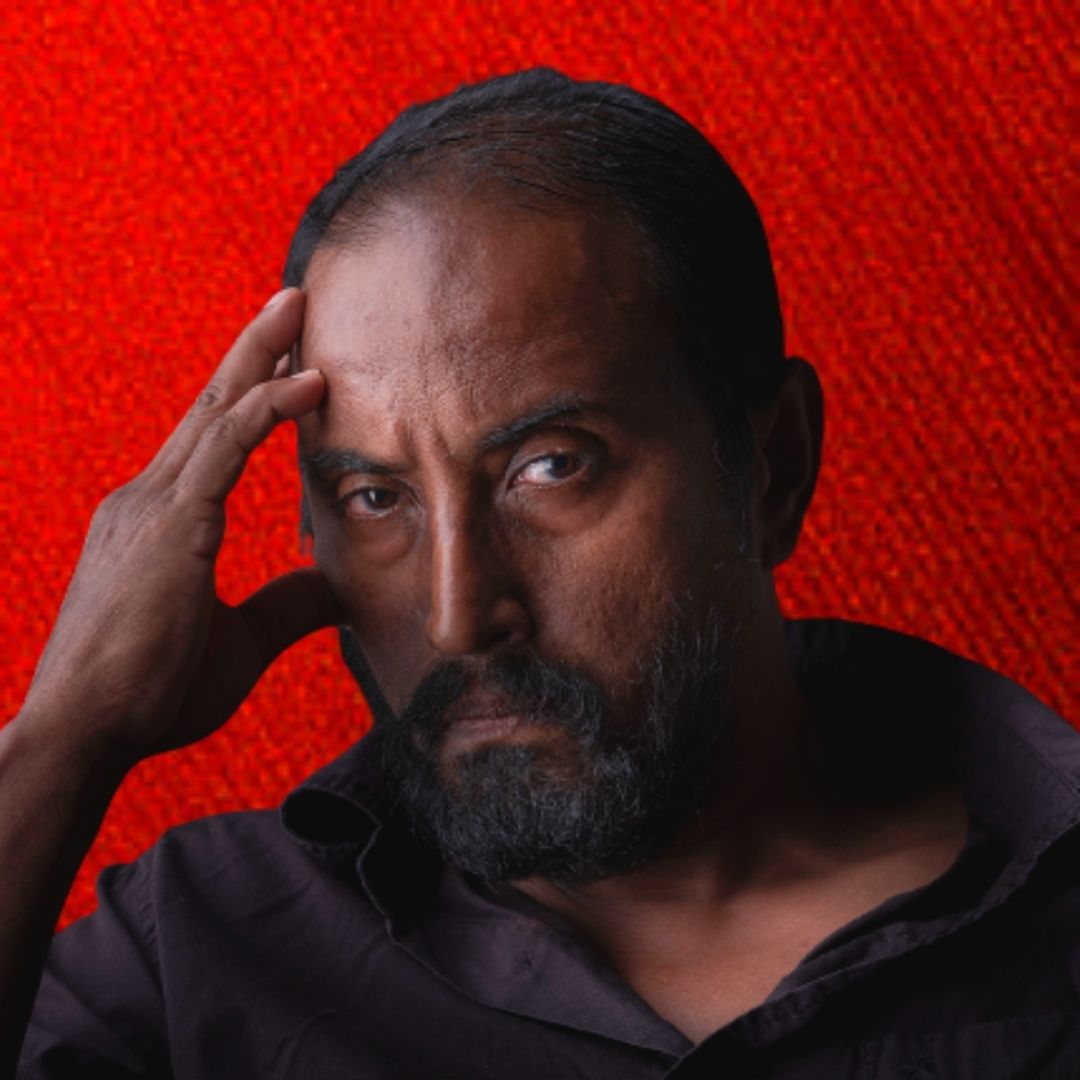

Creatives : Snehadri Sarkar |

While he is a massive sports fanatic, his interest also lies in mainstream news and nitpicking trending and less talked about everyday issues.

C P Surendran's latest novel, One Love and the Many Lives of Osip B's plot traces and connects several 'contemporary themes of transgressive relationships, gender politics, nationalism, individual freedom and group rights, fake news and power'.

Journalist turned writer C P Surendran's latest novel, One Love and the Many Lives of Osip B, is a self-reflective and tragic novel. Through a clutch of dramatic characters, the novel's plot traces and connects several 'contemporary themes of transgressive relationships, gender politics, nationalism, individual freedom and group rights, fake news and power.' Its vast canvas encompasses many other issues, including love and vengeance, fear and despotic power, madness and tenderness, love and loss, power and powerlessness. It also looks into human dependency, motivations, and insecurities.

Fourth among his novels, this is being termed as a fictional exercise in "Hauntology," the science that studies the long shadow cast on our lives by the remembered and the forgotten dead, their inescapable influences, sometimes open, sometimes hidden, often rejected as meaningless and inconsequential, but potent in the way they hold us in their grip.

Besides Delhi and post-revolutionary Russia, Oxford and the murky world of Kerala politics are turning locations of this fast-paced novel around Osip Bala Krishnan, who falls in love with his English teacher Elizabeth while studying in Kasauli. Named after Russian poet Osip Mandelstam by his Stalinist grandfather, with whom Osip shares a unique mental condition that often causes him to hallucinate about incidents of Russia in the 20th century, he is determined to find Elizabeth after she disappears. In that process, Osip unravels the secrets of why his grandfather pretends he cannot remember his past.

In this novel, Surendran presents a powerful narrative, thoroughly engaged and insightful into the place of politics, culture and sexuality in the lives of our contemporaries. It is an ambitious work, steering clear of the recent re-mythologising of the Indian past, which has been put at the service of a particular political ideology of resentment, self-glorification and evasion of the realities of the present. It is a novel in the classic realist European mould, committed to the scrutiny of individuals in their relation to society and nation, but written after, and feeling the impact of, the post- Boom work of the Latin Americans and Rushdie's fantastic narratives.

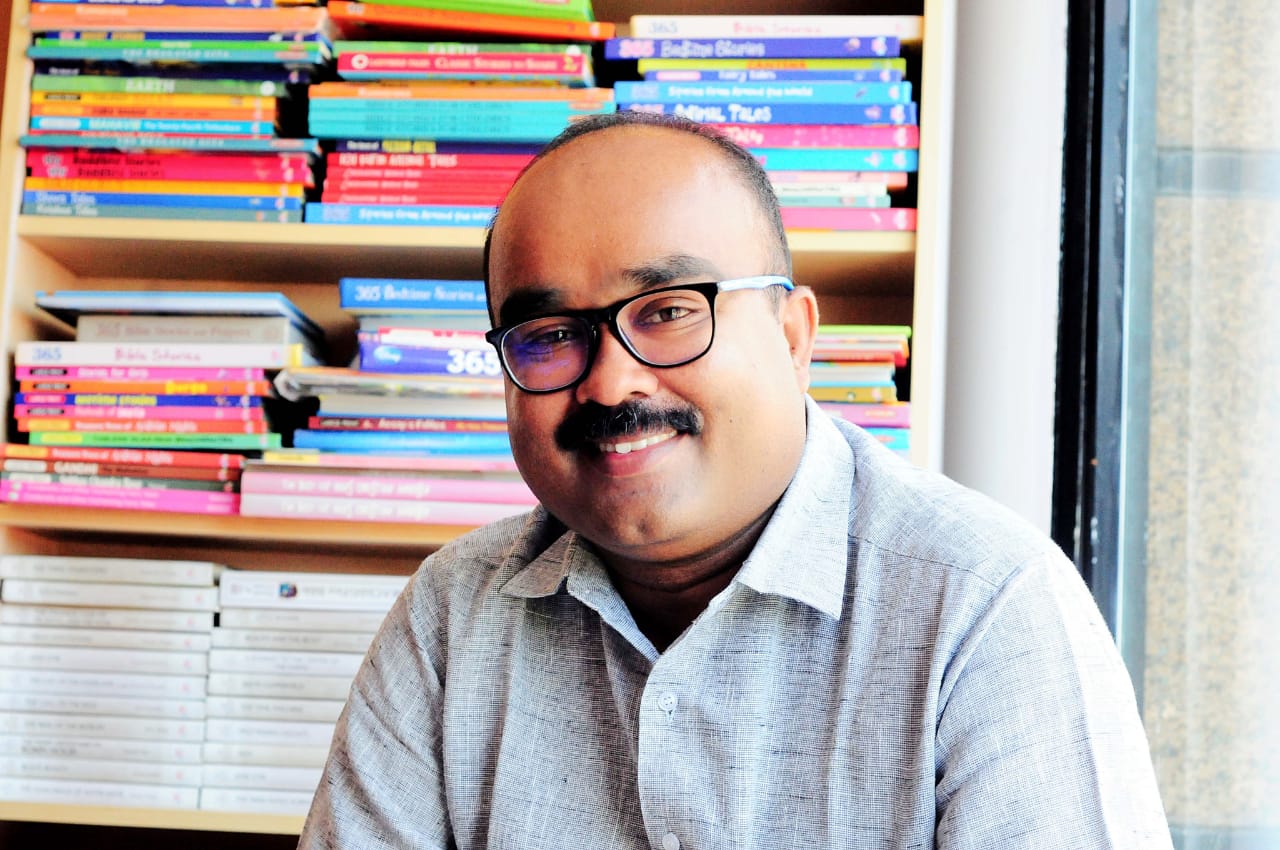

In this freewheeling interview, Surendran, who hails from Thrissur in central Kerala, talks about the novel and his literary journey so far. The son of celebrated Malayalam writers Pavanan and Parvathi Pavanan, Surendran also recounts his evolution as an English poet first and novelist next. On occasions, he is also engaging in soul searching.

Though you have written three novels earlier, One Love and the Many Lives of Osip B stands out as an exceptional work and wins large-scale critical acclaim. Is it marking the birth of a novelist and the death of a journalist?

It's an excellent question. I think One Love is a departure from my earlier works of fiction ( An Iron Harvest, Lost And Found, Hadal, in that order) regarding the seriousness of purpose. I have gone through a few terrible things, such as public pillorying and cancellation on the ground of astoundingly frivolous allegations. This novel partly works for its material, forging of the soul — such as it is—in a special fire in hell. But equally, it is about all of us, caught in a fluid confusion of identity, thanks primarily to social media and a technology that enables by-lined speech without thought. This has mutated our conduct and sense of grievance and rights to such an extent that almost all of us think we are in the right and, therefore, victims looking for or advocating justice. Imagine a situation when every second person you meet is a rebel, across the age spectrum of 17 to 70? Technology has already mutated in us a violent behavioural gene. And if there were a way back, it would happen decades from now, when the Individual would cry and beg for his rights to privacy taken away from him by Google, Facebook, and Instagram.

One Love engages with these complexities dramatised by seven or eight characters, the young protagonist, Osip Bala Krishnan, being one of them.

Now, to go back to your question. One of the casualties of our times is journalism. Because everyone is a journalist now. We do not go to a hospital and expect a compounder or the ward-boy to wield a scalpel. We are looking for a good doctor. Indeed, despite our professed bleeding liberal hearts, we do not look for female or Dalit doctors. We look for a surgeon who knows their work. But we readily accept the idea that everybody can be a journalist if only because they have an opinion to vent, no matter how vicious or ill-thought-out it is. Journalism never was a very healthy plant in India. It was easier to play the liberal card and come across as a hero when you had a weak, relatively less vindictive Congress dispensation. Now that the dispensation is truly hard, the big and small media houses have just given up because they do not believe in much else but the bottom line. The threat to journalism was not always from the government, though. It came from vested interests, including those of the corporate management. We never, in fact, had a great press. The idea of the fearless journalist, for the most part, is a myth. If you and your family are dependent on a corporate salary, your free speech would be self-censored even before you set out, don't you think? I, too, have been guilty of that compromise. Your point that I am finally dead even as this novel is born is well taken. I can only add that my demise as a journalist coincides, unsurprisingly, with the death of journalism in general in this country.

Through the novel, you are introducing a dysfunctional young man who attempts to survive in a deranged world, which according to you, is our world. What are the factors that prompt you to conclude that the world around us is deranged? Is this conclusion personal or political?

The fundamental reason I believe the world around us has changed for the worse is that the hierarchy of values has collapsed. You may stamp me a conservative in this respect and get away from the argument. But take a good look around. The dumbing down that a newspaper (one of the greatest daily influencers of values of our times) like the Times of India ( where I have worked in senior positions for long) started in the 1990s is now finding its logical conclusion across a whole spectrum of social interactions.

As I already mentioned, everybody is a journalist now. Everybody is a poet, too. Everybody is an editor. A theorist. A pundit. A judge. Everybody is the centre of their bubble-universe; the sun shines out of their arse.

To a great extent, access to Google has helped scale up our exposure. In some strange and terrible ways, we are all more knowledgeable than we were before. But look how it has deluded us into thinking we could bring down the greats. There is no more a Hero. That age is gone. They are vandalising the statue of Abraham Lincoln now. They believe Hemingway should not be read because of his toxic masculinity. They consider Gandhi a paedophile. They equate Churchill with Hitler. There is just no context. Despite access to knowledge, there is no sense of history. Despite exposure to suffering as never before, no real sense of sacrifice: you see you could now shape or influence society sitting on your toilet. There is no more a Hero because everybody is a Hero. That democratization does not come without a price. The price is the collapse of a sense of hierarchy. As Baudelaire said in the 19th century, everything is permitted; nothing is confirmed. If you have no existing framework, it is much like being at sea without a compass. You have no bearings. Everywhere, everybody is the centre of his space. Derangement must result at a massive scale, both at a political and personal level. Indeed, even that distinction, the one between personal and the political, no longer exists in any real sense because of the painless ( the toilet revolutionary!) nature of the transition between the two.

It is not uncommon for teenage students to fall in love with their teachers. The search of such students for their disappeared teachers is also uncommon. Then what makes this novel a distinct one?

That is true. What I hope makes the novel distinct is its clutch of characters beginning with Osip Bala Krishnan himself. Why is he named after Osip Mandelstam, the great Russian poet Stalin exiled to Siberia and died of starvation in 1938? Why does his adoptive grandfather, a Stalinist mass murderer (whom his wife Gloria 'thinks' is pretending memory-loss) from Kerala, feel his christening Bala after Mandelstam is an act of expiation? Why do they both suffer from the same delusional world of 20th century Russia? What are the parallels that contemporary Indian society draws in the individual lives of the novel's characters?

Hopefully, the novel is distinct from the rest of the pack because the characters move about in a world that makes them hallucinate normality. It is like touching a stone through water. The world we (and the characters) occupy are weird in a certain perceptual and intellectual way. What I tried to do was to bring home to the reader the unreality of our lives.

Your first novel, An Iron Harvest, revolved around the Naxal uprising in Kerala in the 1970s and the rebellious and disillusioned youth during the Emergency. It also stands as a fictional interpretation of the custodial death of engineering student Rajan and the long and lonely one-person fight his father Echara Warrier waged to get justice. The second novel, Lost and Found, was in the backdrop of the Mumbai terror attack. The third novel Hadal is a fictionalized account of the incidents that conspired around the 1994 ISRO spy debacle in Kerala. You are now evolving to several plots revolving around transgressive relationships, gender politics, nationalism, individual freedom and group rights, fake news and power from such specific plots. How do you wish to comment on this evolution?

Naipaul once said there is no point in writing fiction because reality is more interesting. I find little distinction between the two. There is not much that we can imagine that does not exist. All around us is rich material. But for An Iron Harvest, the other novels are comparatively more fictively spun around. But even in the present novel, in One Love, the plot is not a question of incidents. It is how the process shapes up through hidden channels of language. What interests me in One Love is the pattern of thought and action that, like a ripple in a lake, reaches the far side, seemingly circular, but moving, moving all the time toward their event horizon.

Like Osip Bala Krishnan, you also hailed from Thrissur in central Kerala and a family with known Communist leaders. Are there any autobiographical elements in this novel?

Yes. I believe fiction is the history of a bunch of characters. And the stuff that happens to one's life, directly and indirectly, has a great deal to do with it. We err mostly when we are ourselves. It is from these aberrations that mark our time. In other words, our experiences enable ( or even disable?) us to define our peculiar individual passage through time. We pass through time, each of us an exponent of string theory, making a world of our own in our transit. I come from a literary and political family. But my literature, the way I look at the world through my life, is different from how my family looks at their lives through their words. I imagine my conflict with the world at large is a result of that eccentricity. My late father, Pavanan, was a communist and a selfless man. I am neither. I have great resentment toward him because he left us nothing in the bank. The word and the world he interacted with are redeemable because he approached it with hope and faith. I have neither.

I think if God indeed created the earth, he may have shown the trespass limit with a couple of volcanoes thrown here and there and fuming. But that is the vertical world of God. The horizontal world of society, with its profiteering and greed and deprivations, is a human-made system. Social and political systems are of our making. And the suffering we inflict on each other is, in many respects, more than what God might have intended. But my father would work at it. I have more or less given up on it. Perhaps, all my writing is a drawn-out process of giving up faith. So when we talk about family influences and autobiographical material, we are also talking about how we try to escape these. It is a kind of influence of material family and lineage in reverse.

That is not to say there is no direct impact as well. One of the characters in the novel, Arjun Bedi ( an iconoclast writer and Osip's mentor), is shown as disintegrating in the face of sexual harassment allegations. A similar theme is at work very powerfully in J. M. Coetzee's Disgrace. Or in Philip Wroth's The Human Stain. I had been caught in that wave myself. But the larger question for a novelist is not so much the biographical material to communicate the nuances of that traumatic experience to the reader.

For average Keralites, Osip Bala Krishnan, who transcends geographies and boundaries, may be unfamiliar. But they are familiar with persons like his Stalinist grandfather. Is the disintegration of the USSR still haunting you? Or are you still in search of an alternative to Stalinism?

Stalin killed millions for a beautiful tomorrow. The tomorrow never came, of course. All political leaders will demand of their people great suffering for a better future for their children. It is often for the cause of beauty ( that lovely tomorrow) that we shed blood and ruin lives. Maybe there is no other way. But almost always, too, those who are sure to benefit from the delayed gratification expected of a people are their leaders. Only a very few lead a beautiful day today. I find that unacceptable. The fight against that has little to do with gender or caste or religion: group. It has to do with the Individual. Until we recognise and honour the individuals and their rights, all group formations ( whose leaders are always capable of inflicting violence and generally have a good time) will potentially develop into fascist-like organizations. Simone Weil says somewhere that all organizations will perforce be against the idea of truth. She is talking much about the same thing I just mentioned, I think.

No, the USSR does not haunt me, though it haunted my father to his last day. Like China, or even India, the USSR are, to me, promises that waylaid history. Millions were killed and tortured. Equally terrifying, Stalinist Russia or Maoist China, with its intolerance for dissent and mass surveillance, has passed down from individual leaders and regimes to acceptable social norms.

When a whole society adopts surveillance of each other and calls out and carries out punishments without a minor legal process involved, I think Stalinism has won. We don't recognize it as Stalinism because it is the new normal. That is a fearful thought. Arjun Bedi says as much even as he finds himself powerless to defend the charges against him. How to explain against the norm? Where to begin the story of his fall? With Adam, Eve, and the Apple? The new norms of behaviour that women rights groups (historically justified, of course), for example, prescribe are reformatory ( as in a hostel) in essence. It is a Biblical movement. Except that Yeshiva, the old God, sports a moustache and wears a lilac tunic— as did Stalin— and spouts gender rights. Or else.

In total, the book is not an easy read. You have skillfully interlinked many issues of independent stature or which require further exploration. What do you think? Is it the strength or weakness of the book?

One Love is literary fiction. It is meant to make the reader pause. But I believe what I have tried to do in the novel is a story with a vital suspense element. I would think almost all the characters can raise one's curiosity enough to find out what happens to them next. There is, as far as I can see, a clear beginning, middle, and end.

The plot has hooks and turnabouts. Or so I would like to think. And I believe it is a novel for our times. It is not accessible if you would like to flip pages. Because there are traps laid everywhere, you will need to negotiate the ground carefully. It demands a specific engagement. For example, the year 1938 ( the year of Mandelstam's death) has been mentioned just three times. But a gun that Osip finds under his grandfather's pillow, for example, toward the end, has 1938 inscribed on the handle. Osip B will seize his day with it. 1938 is a conceit yoking together Mandelstam, Osip B, Stalin, and Osip B's grandfather. As I said, the novel demands a certain level of attention.

One characteristic of this novel is its topical relevance. Through the personal experiences and adventures of the characters, you are drawing a picture of contemporary India. Are you still optimistic in this age of rigid nationalist feelings propelled by aggressive Hindutva?

My answer will not make me famous. Given the unimaginative Opposition, general discontent, and the resultant yearning for order and development, in 2024 too, the BJP is also likely to win. So we are travelling toward a Hindu State.

But the point also is, whether the Constitution is secular or not, if a majority of the population wants to assert their faith in overt rituals and rites, it must have a specific historical lineage. Why should a Hindu believe in his God (s) a problem? Only because it takes on exhibitionistic violence. But to take the average north Indian Hindu put off his social and political history and demand he is secular is neither reasonable nor practical. We need to address the Hindu question. Why is he going bonkers? We need to understand the Hindu as much as the Muslim and the Christian. Instead of that attempt at understanding, we jeer and taunt the Hindu.

You talk about the country's corrupt and monstrous media enterprises to which you too were part as an employee for a long time. Is there any light at the end of the tunnel? How can the Indian media regain its losing accountability?

I have already partially answered this question. I can only say that the collusion between the big media and the Indian State goes back to at least Gandhian times. But at that time, we believed the interests of independent India and the media were complementary and benefited all. That turns out not to be the case. The corporate media in India is not founded on values, say, like the NYT is by and large. It is founded on lip service to values. I have been a part of it. And I have secreted away good stories and splashed planted stories. And I did it because I had to pay my bills. So I am no one to judge.

But until the journalist community as a whole is financially secure, I do not see any tremendous sustainable efforts at an independent media narrative. In a genuinely capitalist and crony-free market, perhaps our media houses too might fare better. Profit then would be a matter of excellent reporting and feature-writing. But that is too much to expect now. We see the last years of the print, anyway. And the online outlets, especially the revolutionary ones, live on the charity of some generous millionaire.

The aspiring godman Anand in the novel gives a glimpse of the murky market of religion and spirituality existing in India and is now expanding beyond borders. As the son of a well-known rationalist and a journalist who observed the faith industry from close quarters, what is your take on godmen and god women, especially their continuing clout over governments and policymakers?

Recently Mr Monson was arrested in Kerala for cheating and fraudulent trade in antiques. I have great admiration for him. To a people who never tire of portraying themselves as highly cynical and rational and logical, Monson sold stale stuff worth crores. That takes some talent. The reason he could do it is old: an abiding belief in miracles. Here's Solomon's sword. Or some such. Or Cheraman Perumal's loincloth. And we believe it. Not because it is possible. Because it is impossible, it is impossible that someone lies to you or cheats you with odds like that. Monson knows that humans can believe only in impossible things, in miracles. In One Love, Anand offers miracles: salvation. Sit with me, breathe with me, pray with me, and you will be saved; good things will happen to you. It is impossible. But that is what gods, and temples, and Amritanandamayi, and Sadguru are all about. They are just a step above ( or below) Monson. But what they are selling is hope. It is a very human thing. Anand is a false Godman, but being false, he represents hope. I don't think any amount of the Pinarayi Model of communism will alter that. Expect more Monsons.

Are the questions of identity, nationality, and beliefs relevant in cosmopolitan people who get educated and live beyond borders and intermingle with people of different cultures? Is cross-cultural relations a solution to the issue of rigid nationality? Is there any scope for life beyond nationality and identity?

As mentioned in the novel, the very rich have no nationality. You will not find the Tatas or the Elon Musks of the world campaigning for group rights. Neither will the very poor. They don't have the time. With their tiny houses gifted by their fathers or husbands and leisure for reading and writing, the middle classes have real problems. Like Osip in the novel, I am at home nowhere. I dislike India except for the hills. But when I am abroad, I dislike those places and their visibly more good living even more. I cannot talk to others, but I find the idea of identity, place, religion, culture, and politics pointless. Almost all of it, we are born into, without a choice. Now to make another choice across that spectrum is such pain if you are a thinking person. I cannot envision how the identity question plays out in Nordic Europe ( a place so capitalist, it has put into practice Utopian communist ideals). My thought on this matter is that the identity question is essentially more existential than cultural. To be human and to be dying every moment is more problematic than being a groupie rebel. But one's material needs must be taken care of, which is where the identity problems all, after a fashion, boil down to.

Are Osip's desperate search for Elizabeth Hill and his claim that he was obsessively in love with her quite odd? Will the present generation find it realistic to travel from one city to another and across countries to the lover's hometown?

The obsession is odd in so far as it makes Osip take decisions that shape his destiny. As you said earlier, boys fall in love with their teachers all the time. But to take it to the next level is when a boy or a young man becomes a character. I know people who have moved cities and countries to persist in the illusion of love. Love is a strange thing in that it exists only now and then. That is its magic too. Osip's entire life is shaped by his travel, his journey after the holy grail, Elizabeth. But it is not just Elizabeth. Through that journey, he discovers his family secrets, becomes a journalist in a fake media outlet, and confronts the great question of life authenticity. So, it is love on the one hand. On the other, it is a journey toward himself.

You hail from a family of writers, and your parents found prominent places for themselves in the history of Malayalam writers. Have you attempted at any time to write in Malayalam?

I was pretty good at Malayalam till the fourth standard. Then something seemed to have happened, and I took refuge in English. Somehow I could think unthinkable things in English. I can read old Malayalam easily, but not the alphabet too well in the new form. I have read quite a few Malayalam novels and poetry and am familiar with its tropes. No, I have not tried writing in Malayalam, and now it's too late. This is the last lap. Can't run back to the starting point now.

The iconic journalist C. P. Ramachandran was your uncle. What role did he play in making you a journalist first and a poet and novelist later?

He was a great intellectual, a very arrogant, and a courageous man. And a terrible father and a domineering uncle. But he set the standards for us. I mainly was a timid boy, but he had a presence that turned everyone into less than nothing, anyway. In retrospect, though, he was trying to say, grow up, the world is more prosperous than you think, read, get somewhere, be something. But it was not easy measuring up to his standards. He greatly influenced all of us, brothers, sisters, and cousins. More than our fathers, he was the man we looked up to and consistently fell short. I guess in very many ways, he was the last of the great Nair patriarchs, though he would not have agreed to that idea of himself. He had a very keen understanding of the world and none about his own family. He tragically miscalculated his importance post-retirement and his role in his illustrious sister's house in Parli, where he had retired, he said, to drink himself to death.

The journalist, K. A. Johnny, had done a great interview with him around that time. Except that my uncle's money ran out on him before he could realize his objective. My uncle introduced me to Shakespeare and Gerald Manley Hopkins and Bernard Shaw, and Will Durant. He was the first Malayalee I thought I knew who could use the English language precisely like a harpoon, and he could coin a phrase that turned your thoughts, and you mumbled to yourself, ah, there is another way of looking at the same thing, and it is beautiful, too. I think the little streak of rebelliousness that I have was his gift. When he died, I was among the people who carried his body, and when I lifted his head, it weighed a ton. It is the heaviest weight I have lifted.

Which is the best literary medium do you prefer? Poetry or fiction?

I believe poetry comes more naturally to me. Fiction is tough. Just very, very tough. Not just the physical labour ( this novel took seven years ); but the connections and the passages in the future and back, and the language part of it. The novel is a process. You have to show things as happening — even if it is in the past. So the language must be explained without being boring, and each line is a step forward. You can't sort of ease up. It is challenging, all right. Poetry is four lines. Or 10 or 12. An image could carry off a whole thought. There has to be a movement here as well. But it is not process-driven. It could be associative. It could draw on auditory resources.

Do you wish to be identified as a Malayalee always in voluntary exile?

I don't know if I have a choice. When I visit Kerala, I find it a very green, relatively clean place that is hard to understand. I don't understand the arrogance of the Malayalee, for instance. The average Malayalee is not even well-read, contrary to his estimation of himself. But his natural flair for venting an opinion is impressive. He is also intellectually unequivocal in his ideological positions. I find that even harder to accept. He naturally believes the Left is better than the Centre and the Right. But he has no clear arguments besides his habituated ideas. He believes in a house with a wall, a car, two children, and a wife, and then he would speak with great conviction about revolution. He is not tolerant of an alien idea or custom. And the place is too warm.

If I had my way, I would disappear among the cool blue hills of the North. But then the North is not the South, and I can't speak Hindi well either. So, let's see. Munnar is a possibility. Or a cottage in Wayanad. I have a feeling I might die alone in the hills.

Also Read: My Story: 'Being Around Sanjana Made Me Discover More About Myself, My Sexual Identity'

All section

All section